Why photography can’t ignore the beholder’s share

In a 1909 interview Matisse explained the invention of photography released painting from any need to copy nature. As a consequence, art could do away with surface detail and capture hidden truths.

For me, the advent of flawless digital cameras has meant for a while I have been struggling with my photography, unwilling to pursue an activity where there can be little technical improvement or much that I can photograph that can’t be photographed by anyone.

It’s vaguely embarrassing to learn three painters more than a hundred years ago were grappling with this problem.

I am slightly relieved that it took a Nobel Laureate, Eric Kandel, to expose my ignorance, in his extraordinary 2012 book, The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind.

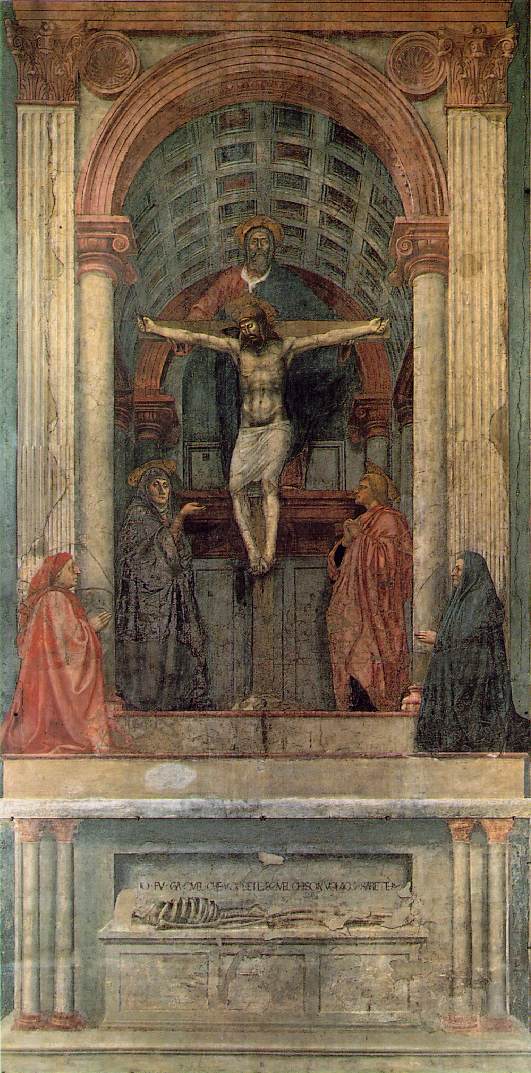

Kandel’s book introduced me to the art historian, Alois Riegl, who stressed the importance of the beholder’s participation or beholder’s share for the completion of a painting, something that stripped from art “its pretension to achieve a universal truth”. Reigl’s book, The Group Portraiture of Holland , compared 16th c Italian art to 17th c Dutch art. Reigl argued Italian art sought to depict “the eternal truths of christianity and to elect idealised feelings of piety, faith, pathos, fear and passion” .

In contrast to this hierarchical self-sufficient (internally coherent) art where “the viewer’s participation is not required to complete the story”, Dutch art called for external coherence “in which the viewer’s participation is critical for completing the narrative and the picture”. Reigl argued Dutch democratic values of mutual respect and civic responsibility created the need for artists to create artworks where people within paintings acknowledge each other and the viewer as equals.

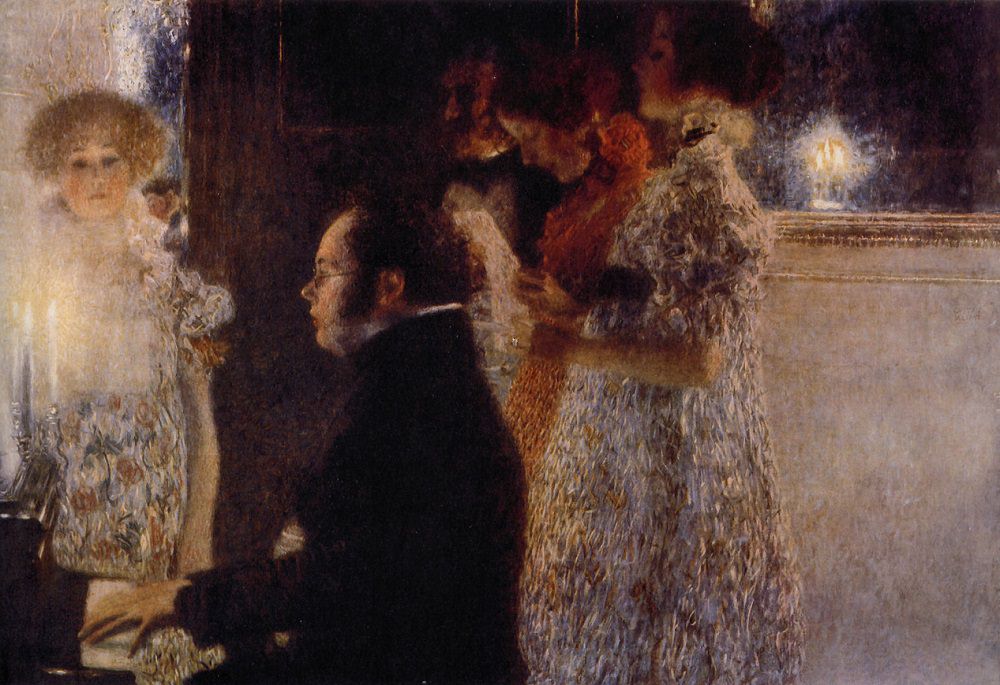

Kandel notes the art critic Wolfgang Kemp extended Riegl’s position to Klimt, Kokoschka and Schiele, arguing they all “wanted to create art with external coherence … based not on the viewer’s social equality with the people in the painting, but on the viewer’s emotional (empathetic) equality with them. Whereas the Dutch painters invited the viewer into the physical space of the painting, the Viennese invited the viewer into the emotional space of the painting. ”

In Klimt’s painting below, “Like the Dutch paintings, it is entirely committed to an ‘ethics of attention’: the attention of Schubert to the music, the attention of the four listeners to Schubert, and the attention of one of the listeners (the woman at the left) to the viewer, thereby bringing the viewer into the picture and completing the circle.”

So if man has been cast out of a world of hierarchical authority, no longer believes in civic responsibility and mutual obligation, and feels emotionally alienated, there are no universal truths that can be shared, so there is nothing to photograph. Or is there? I don’t have the answer for this so it will keep me occupied for while, particularly now that I have learnt about the beholder’s share.

Leave a Reply